- The Action Digest

- Posts

- 💥 To Launch Something New, You Need "Social Dandelions”

💥 To Launch Something New, You Need "Social Dandelions”

The 4-Step Playbook That Launched Pinterest, Harry Potter, and the GameStop Squeeze

In our last edition, we learned the social science that explains why great ideas like new books, apps, or social movements, mostly originate from within small communities.

If you haven’t read it yet, and you’re curious what Airbnb, Iowa’s corn farmers, and Fifty Shades of Grey have in common, then you check it out here.

Today, we’re going to turn this law into a playbook by answering four key questions:

What type of community is best for launching a new idea?

How do you find the right community to introduce your idea to?

Which members of a community should you talk to first?

How can you maximize the odds that a community will embrace your idea?

With a little help from an unruly financial subreddit, a Midwestern blogging conference, and a 1950s farm report, all shall be revealed…

P.s. More action awaits you in our archives, including how Steve Jobs cultivated great taste, the personality trait shared by 1381 millionaires, and the study that revealed what successful founders, scientists, and terrorists, have in common.

1/4 What type of community is best for launching a new idea?

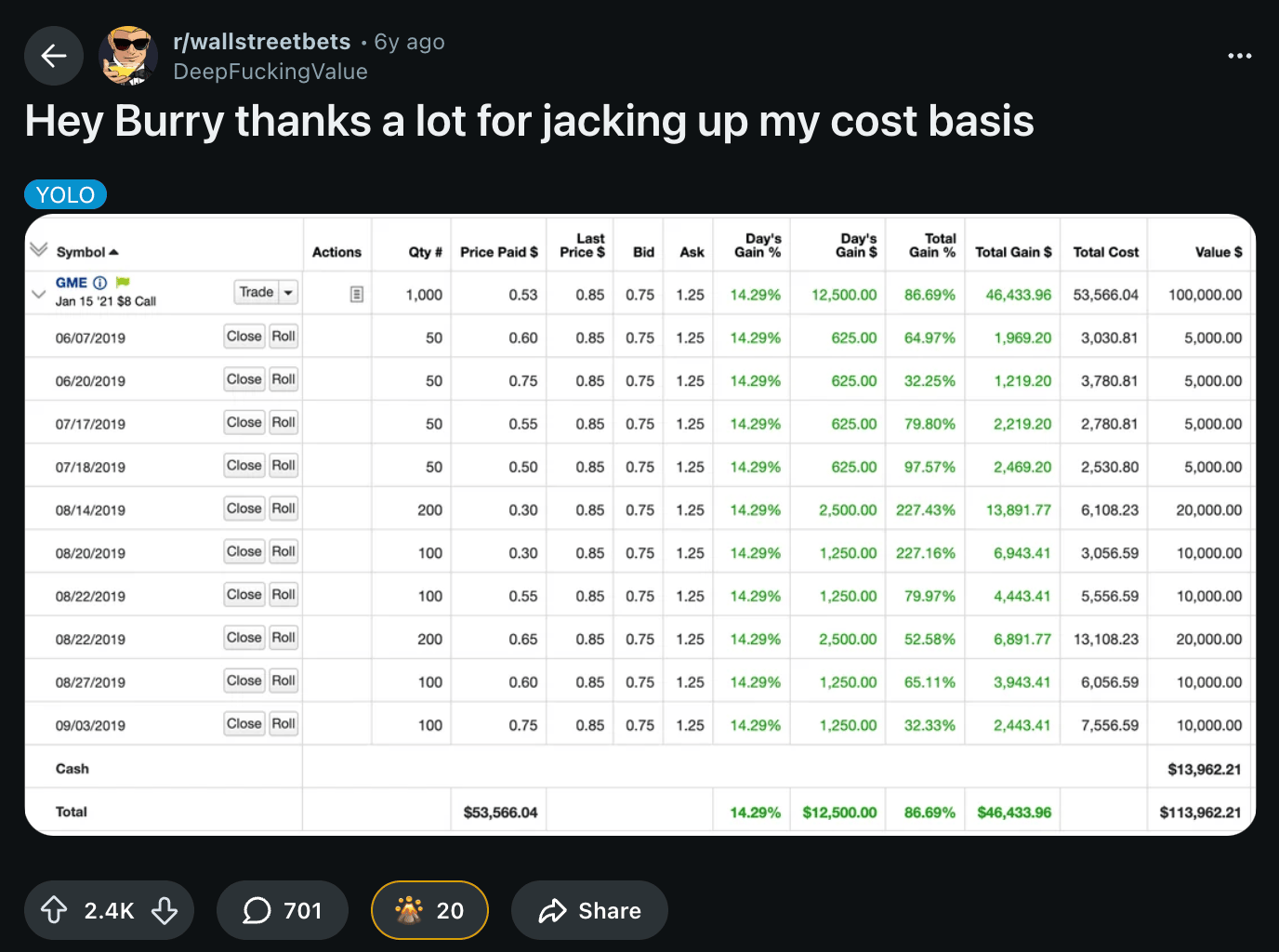

In September 2019, a small-time financial trader named Keith Gill posted a screenshot online that would rock the financial world. It was a receipt for his $53,000 stock trade in the dying video game retailer, GameStop (GME). Much like a new fashion trend or social app, Gill’s trade was a big idea that he hoped would catch on.

Gill saw that GME was one of the most heavily 'shorted' stocks, meaning many powerful firms were betting on its collapse. He realized that if the company just stabilized a little, and enough new buyers showed up, those 'shorts' would be trapped. As the stock price rose, they would be forced to buy shares to escape their trade, creating a feedback loop where buying would beget more buying, sending the price violently higher.

Gill’s trade was a complex contagion, the kind of opportunity that only works if lots of other people decide to believe at the same time.

If he had posted his trade in a conventional investing community—say, a cautious value-investing forum or a personal finance subreddit—it likely would have been dismissed as reckless, over-concentrated, or just plain dumb. But Gill chose to post his screenshot in a subreddit called WallStreetBets.

WallStreetBets was a rowdy arena of traders who wore their risk tolerance like a badge. Posting your entire net worth in a single trade was a form of entertainment. Members were openly hostile to financial gatekeepers, fluent in an absurd meme language, and narrated their trades in public—turning the markets into an ongoing soap opera.

So when Gill dropped his GameStop trade there, it was like the flap of a butterfly wing that would cause a hurricane. People watched his updates, first with disbelief, then with curiosity, and eventually with admiration as the trading volume in GameStop doubled over the course of the coming year. The number of members following WallStreetBets also doubled in that same timeframe.

A narrative began to form: retail underdogs versus smug hedge funds, diamond hands versus paper hands. Just a few months later, GME’s volume was over 20x higher from when Gill first posted, with WSB growing to over 6 million members. An idea that began as an online screenshot quickly vaporized $6.8 billion from one of Wall Street’s biggest hedge funds in a matter of days (an injury from which it never recovered, forcing it to close its doors 18 months later).

Gill had found the one community capable of turning his fragile insight into a world-shaping event. Not all communities are created equal in this regard. WallStreetBets had several hallmarks of a high-gain idea community—the kind of place that can amplify a powerful idea.

WSB shares much in common with other high-gain communities such as the schools and universities that launched social apps like Facebook and Snapchat, the Bronx block parties that gave birth to hip-hop, and the online fan fiction forums that launched Fifty Shades of Grey and more recently, Alchemised. Here are a few of the commonalities they share:

Appetite for risk. Remember that you’re asking people to take a risk when you introduce them to a new idea that’s a complex contagion. Communities that are more open minded and risk tolerant are likely to be receptive to taking on that risk. On WallStreetBets, high-risk bets were the norm. Look for a community that already likes being early and experimental (heck, maybe even a little unhinged)—because those are the people who will actually try something new.

Strong group identity and a clear “other”. WallStreetBets framed itself as degenerate underdogs in a rigged system, with hedge funds as the obvious enemy. Buying and holding GME became a way to perform membership in the tribe. In any niche, if your idea can be adopted as a badge of “people like us” and, implicitly, “not like them,” it can gain an emotional momentum that can’t be stopped.

A native storytelling format. There was a common post format on WSB: position screenshot, outrageous caption, unfiltered commentary, then periodic updates. Keith Gill slotted his trade perfectly into that template. A community that has established “story shapes” (build logs, challenges, before/after posts) that your project can inhabit will make it much easier for your idea to spread.

Insider language. “Diamond hands,” apes, tendies—WSB could compress complex feelings about risk, loyalty, and defiance into a few shared symbols. The GameStop trade became shorthand for a whole worldview. For your own launch, communities with lively in-jokes and visual culture can turn your idea into a meme-able token, making it easier to pass along than a carefully worded pitch.

Passionate, single-topic focus. A community that is deeply passionate about one subject is primed for new ideas within that niche. On WallStreetBets, that passion was high-risk trading. A shared passion means members are all paying close attention to the same things, allowing a related idea to capture the entire group's focus quickly.

Ultimately, Keith Gill found the perfect “idea–community fit.” Not only did he choose a community that would be receptive to his idea, he chose one that had all the cultural forces to take it mainstream.

So how do you find your version of WallStreetBets—the community whose instincts, rituals, and values make it the natural amplifier for your idea? That’s where we’ll go next.

2/4 How do you find the right community to introduce your idea to?

In 2010, Ben Silbermann and his cofounders had a brilliant idea of their own. At the time, almost every app wanted you to generate content from your own life—your status, your photos, your thoughts—to create. But Silbermann believed people would also want an app to gather content based on their own taste—recipes, designs, articles—to curate and collect.

This idea was called Pinterest.

The good news is that Silbermann was in the perfect place to launch it. He was in the exact same tight-knit Silicon Valley community that launched Twitter, YouTube, and PayPal. Silbermann and his cofounders emailed hundreds of friends and colleagues in the tech community and then excitedly monitored the analytics dashboards for virality. But as the days wore on, their hearts sank.

Everyone tried Pinterest, but few came back.

What gives? Silbermann followed our advice from last edition—he targeted a niche community with wide bridges. He even targeted one that had a proven track record of launching big new ideas. Why wasn’t Pinterest sticking?

Out of desperation, he tried loading up Pinterest on devices in the Apple Store in Palo Alto, and saying loudly, "Wow, this Pinterest thing, it’s really blowing up"... to no avail. As he started to question his faith in his great idea, he noticed something interesting in the dashboards.

A small cluster of users were coming back to Pinterest. But they weren't tech bros asking "What should my startup's pitch deck look like?" or "What's the ultimate desk setup?”, these people were asking questions like “What do I want to eat?” and “What do I want my house to look like?” The most engaged persona seemed to be women from the Midwest, much like his own mother and her friends in Des Moines, Iowa.

Upon realizing this, Silbermann gave up on the tech community and targeted a different one. He flew to Salt Lake City to join a few hundred female design and lifestyle bloggers at a conference called Alt Summit.

At Alt Summit, the reaction was totally different. As Silbermann talked with attendees, they immediately lit up. He stayed closely connected with them after the event, learning from their behavior and shaping the product around it.

This relationship would eventually lead to a simple experiment: bloggers would each make a themed Pinterest board, write a post about it, and pass the baton to the next creator. This became the “Pin It Forward” campaign, and it spread fast—pulling Pinterest into the center of a highly connected blogging community and giving the product its first real wave of growth.

The takeaway here is simple. Don’t give up on your idea just because one community rejects it. The perfect group may still be out there. And the right community may come as a surprise. The cofounders of Pinterest had no idea their app would strike a chord with female bloggers from the outset. They noticed some unexpected sparks of interest and then followed the smoke until they found the fire. Trial and error is an acceptable strategy when it comes to finding the right seed community.

But let’s say you do have a wide-bridged network in your sights, which members do you need to win over first?

3/4 Which members of a community should you talk to first?

In our last edition, we learned about Iowa's farmers in the 1930s who were facing a looming drought and severe famine. They famously rejected a 'hybrid corn' seed that was a perfect, life-saving solution, with less than 1% adopting it at first even though 70% knew about it. We learned this was because the new seed was a 'complex contagion'—meaning they didn't need more information, they needed social reinforcement from other farmers in their network before they were willing to take the risk.

But the story doesn’t end there.

As I was researching this case study, I stumbled across a research bulletin from 1950 that went deep into the adoption arc of hybrid corn. As part of the researcher’s analysis, they wanted to know whether certain farmers adopted hybrid corn faster than others. And if so, what made those farmers special? Was it something about their personality, their financial situation, or perhaps their social standing?

They found that there was indeed a huge difference between those who embraced hybrid corn earlier versus later. First off, some of the most obvious assumptions were wrong. The researchers found that being a "leader" in the community—someone who held office in a local organization—had no relationship to being a leader in adopting the new corn seed.

So, what did make the early adopters special? The key persona was a farmer who was both open-minded and socially active. The faster adopters were significantly younger—where the fastest had an average age of just 38, while the most resistant farmers averaged nearly 56.

Education was another massive factor: almost 66% of the fast adopters had more than an eighth-grade education, and almost 33% had some college experience. But in the most resistant group? Not one single farmer had gone past the eighth grade.

The faster adopters were also more hungry for knowledge—reading on average, eleven times more bulletins from the state's agricultural college than the late adopters.

But many of the biggest differences between the early and the late were found in their social habits. The fast adopters simply showed up in more places, more often. They belonged to three times as many organizations, took more trips to the "big city" (Des Moines), and were more likely to attend movies, athletic events, and other commercialized recreation. They were the most active participants in their community.

This would suggest the people we want to connect with first within a community are those who are most receptive to new ideas and also those who are most socially active.

But can we trust the findings of a study conducted 70 years ago on an event that happened 20 years even prior to that? Modern sociology studies suggest that yes, we can.

In 2016, researchers at Princeton, Rutgers, and Yale Universities published a study that echoes our 1950 bulletin. But they didn’t study the spread of crops, they studied the spread of social norms in 56 New Jersey middle schools. Specifically, they wanted to see if they could get a new idea off the ground—an idea that's notoriously difficult to spread in a middle school: that everyday bullying and conflict just isn’t "cool" anymore.

And provided they could make this idea popular, and measurably reduce instances of bullying, which students would be key to making it happen?

Half of the 56 schools were designated as the control group—they just went about their year as usual with no interference by the researchers. In the other half of the schools, the researchers came in and randomly selected a small "seed group" of 20 to 32 students. They encouraged each seed group to become the public face against bullying. The kids took charge, designing their own anti-conflict posters, creating hashtag slogans, and handing out bright orange wristbands to other students they saw doing something friendly or stopping a fight.

At the end of the full school year, the researchers checked in to figure out whether conflict decreased in the seed schools relative to the control group schools.

The results were impressive. Across the board, the schools with the anti-bullying program saw their official disciplinary reports for peer conflict drop by an estimated 30% over the school year.

But here is where our corn farmers come back in. The 30% figure was just the average across schools. Some seed groups were dramatically more successful than others. The researchers found that the success of each school’s program depended almost entirely on who was in its seed group. There was a specific type of student who had an outsized impact. The more of this one persona a group had, the more powerful that group was at changing the school's norms and reducing conflict.

It wasn't the "popular" kids, at least not in the way we usually think. Just like being a "leader" in a farm bureau had no bearing on adopting new corn, the researchers found that traditional, subjective measures like "popularity" or "friendship" weren't the magic ingredients.

The students who mattered most were the ones identified by a very specific survey question: "Who did you choose to spend time with in the last few weeks?". The most influential students were ones who spent time with the most number of people. They were the most socially active—those who were present in more social interactions than anyone else.

You can think of these kids as “social dandelions”. Just as a dandelion is one of the most common and widely seen flowers, these students are the ones who are most present and visible to the most different people across the entire social ecosystem.

The effect of social dandelions was massive: in schools where the seed group had the highest proportion of these key students, the program reduced bullying by 60%—double the average.

Many of the most influential people in a community are the most present.

Dandelions are the people you need to win over first.

This is actually the strategy that Bloomsbury used to seed one of the most viral ideas of all time—the first ever Harry Potter book. In their initial publishing release they only had 500 books to give away for promotions.

What community is the most effective target for a children’s book, they asked?

Well, where did children go to read books in 1997? Libraries of course. And within that community, who are the most present and well connected dandelions? Librarians! So Bloomberg gave away 300 of their 500 books to librarians, who then recommended Harry Potter to kids and parents. By effectively seeding the idea in dozens of targeted communities across the UK, the stage was set for the explosion in popularity and the powerhouse literary universe we all know of today.

Now you know which type of community to target, how to find the right one for your idea, and who you need to talk to—one question remains.

How do you convince a dandelion to adopt your new idea?

4/4 How do you convince a dandelion to embrace your idea?

In 2006, Scott Belsky and his team had done everything right to get their great idea off the ground. Almost.

They had created a portfolio website called Behance that allowed creative professionals to showcase their work.

Scott was deeply embedded in the design community that Behance was founded to serve and he was pitching dandelion designers to upload their portfolios to his site.

Despite following all three steps in the playbook we’ve outlined so far, it still wasn’t good enough. “Inviting top designers to showcase their portfolio on a website they could barely pronounce and had never heard of was a fruitless endeavor,” Scott admits. “Nobody cared or had the time.”

That’s when Scott’s team realized Behance was a complex contagion. To engage with it, designers had to pay an adoption cost. The cost of using their site was the effort and time required to create an entire portfolio using unfamiliar software.

Instead of taking no for an answer, Scott just paid the adoption cost for them.

“We contacted the 100 designers and artists we admired most and instead asked if we could interview them for a blog on productivity in the creative world. Nearly all of them said yes. After asking a series of questions over email, we offered to construct a portfolio on their behalf on Behance, alongside the blog post. Nobody declined. This initiative yielded a v1 of Behance that was jam-packed with projects, each from 100 top creatives, built the way we wanted. This manual labor was the most important thing we ever did.”

If you’re pitching an idea to a dandelion that requires any effort whatsoever to engage with—your job is to figure out how to lower that effort to the maximum possible degree.

Take every risk off the table you can think of, including time, money, effort, decision fatigue, and reputation. Make it as cheap, fast, easy, and safe to engage with your idea as possible (at first!).

Follow the four steps in this playbook and you’ll give your great ideas a fighting chance at reaching escape velocity.

Because as we like to say around these parts, it’s not about ideas, it’s about making ideas happen.

Final Calls To Action

Want to understand the implications of recent advances in tech, culture, and product design? If so, Scott Belsky’s monthly analysis is essential reading. In his latest November edition, Scott explores why content creators and artists are taking a different approach to AI, and whether some newer tech unicorns may be in fact be rabbits in disguise.

Looking for a way to elevate your creative process using good ol’ fashioned Pen and (80lb Via Vellum Cool White) Paper? Replenish your supply of Action Method notebooks—the essential toolkit that thousands of creatives rely on to work with a bias toward action.

Want an easier way to connect with us and the Action Digest readership? This newsletter goes out to thousands of smart and effective readers each week—what would happen if we could tap into our collective intelligence? To find out, we’re thinking about starting a group! If you’d be interested in joining then reply to this email/post with “count me in” or something similar :) — thank you to everyone who has raised their hand already, more details to follow soon.

Thanks for subscribing, and sharing anything you’ve learned with your teams and networks (let us know what you think and share ideas: @ActionDigest).

How successfully did we launch the ideas in today's edition? |

This edition was written by: Lewis Kallow || (follow)  | With input and inspiration from: Scott Belsky || (follow)  |